Fuseli and the perceptions of womanhood

by Claire Ding

Last December, I was fortunate to see the work of Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), one of the most eccentric 18th century European artists, at the Courtauld gallery. The exhibition, Fuseli and the Modern Woman: Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism, explores notions of sexuality, gender, and womanhood, which were constantly being challenged and reshaped during the Victorian era. An array of his private drawings were displayed, foregrounding different courtesans and his wife, Sophia Fuseli, as the centre of attention. Breaking away from female stereotypes of submissiveness and maternal virtues, Fuseli’s work of the Modern Woman destabilises traditional understandings of womanhood. In my opinion, however, his reimagination ultimately does not seek to empower women and continues to confine women in archetypal roles, subjugating them to the aesthetics of an alternative, but nonetheless male, gaze.

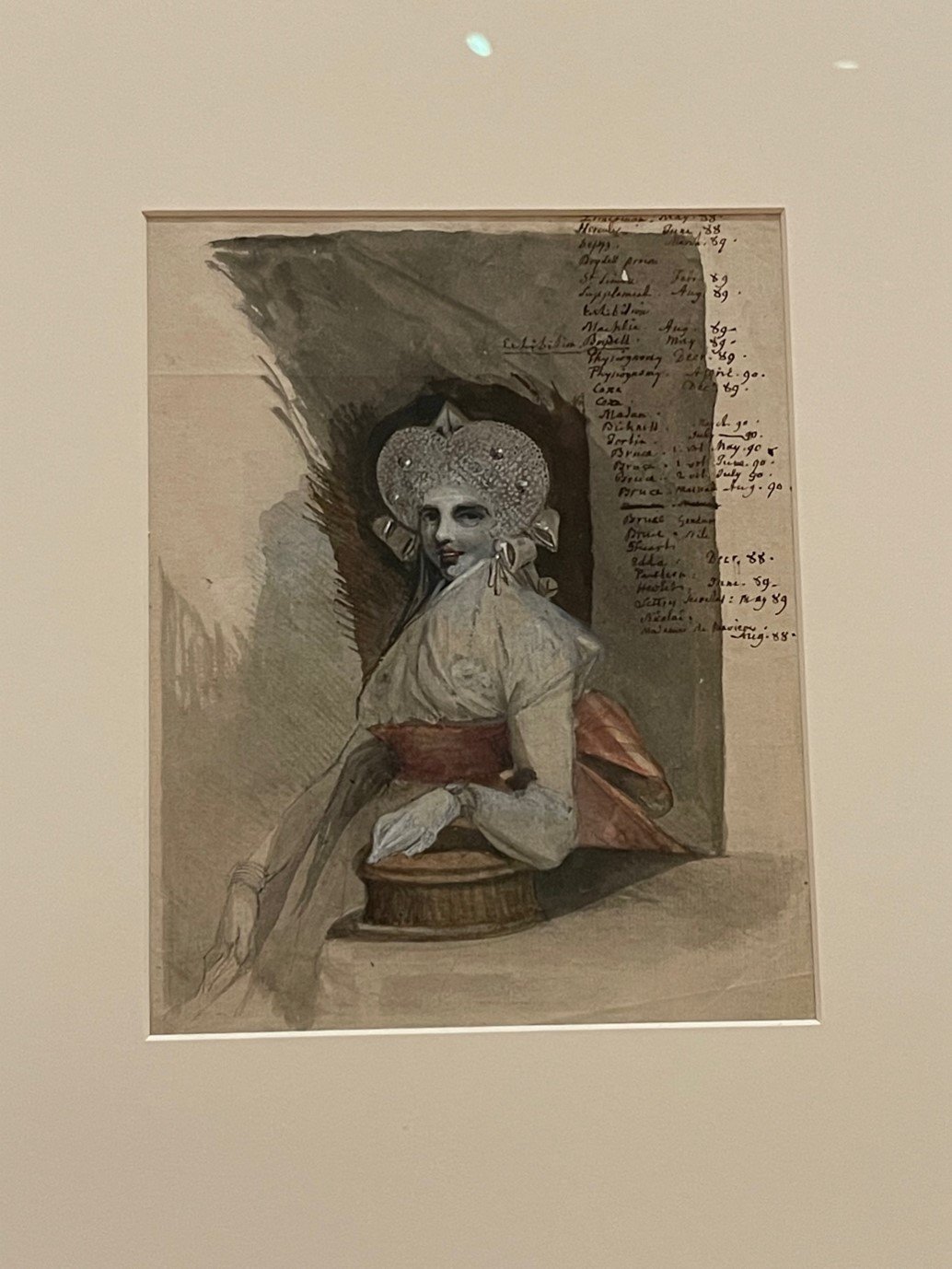

Fuseli does, however, showcase the multiplexity of womanhood by subverting female archetypes through the lense of the appearance and clothing of courtesans. In ‘Sophia Fuseli, Standing in front of a fireplace’ (1791), Fuseli casts his wife in an elaborate drapery with a complex hairstyle, reminiscent of a courtesan. This depiction is further reinforced by her pink cheeks and red lips, and green facial complexion recalling concurrent tuberculosis aesthetics. Interestingly, Fuseli situated Sophia in a domestic setting, marked by the fireplace, which is affiliated with notions of maternal love and care, creating a stark contrast with an erotic appearance associated with women of a dubious moral character and wild sexual passions. Such oppositions can also be seen in ‘Sophia Fuseli, Seated at a table’ (1790- 91). On one hand, Sophia exemplifies sexual immorality, portrayed by her seductive gaze, voluptuous lips and translucent drapery; the sewing basket next to her, on the other hand, associates her with virtuous domesticity. By doing so, Fuseli converges and distorts Victorian female archetypes of the angel in the house and the fallen woman, thus freeing perceptions of womanhood from conventional understandings.

Sophia Fuseli, Seated at a table Sophia Fuseli, Standing in front of a fireplace

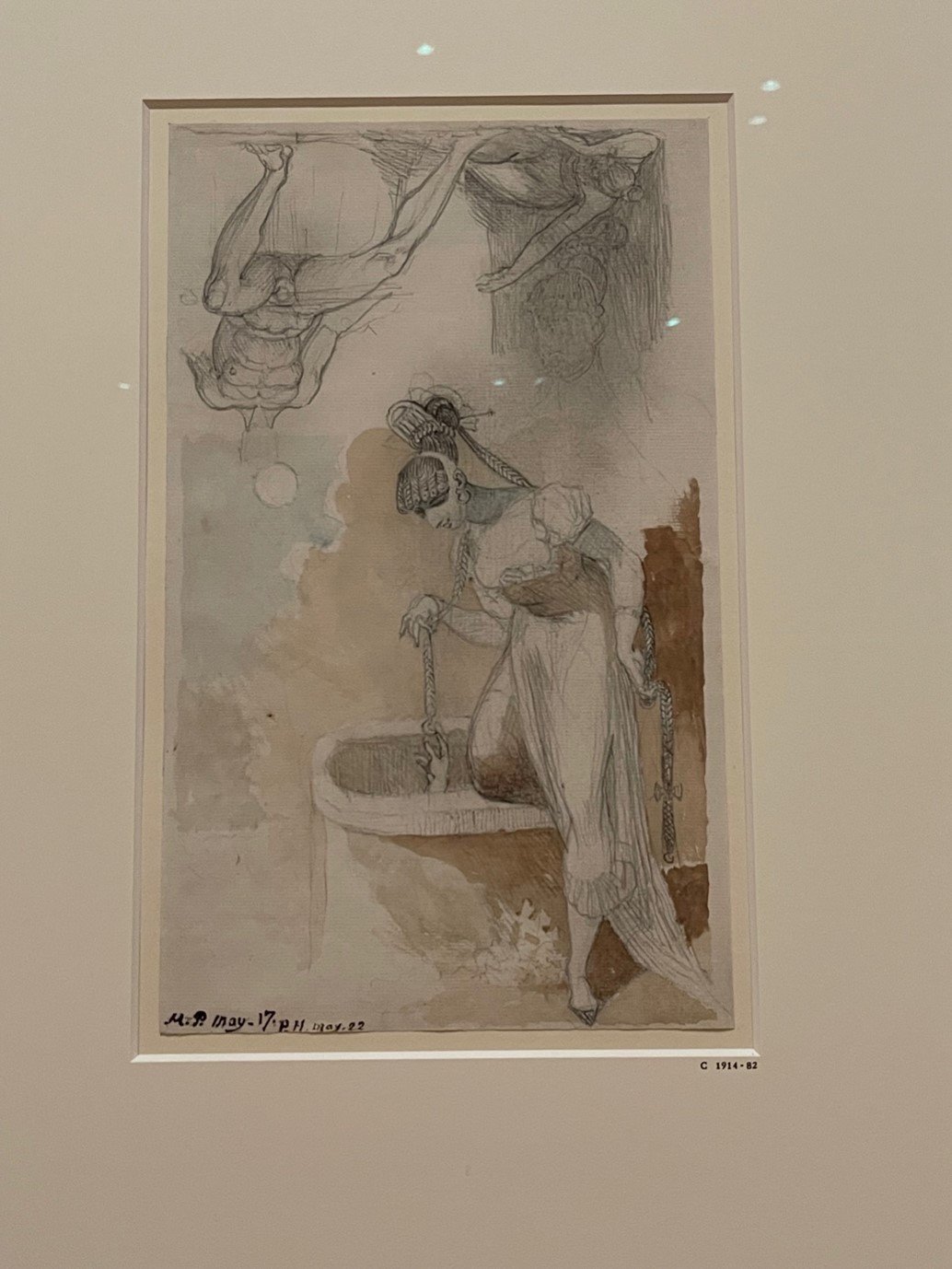

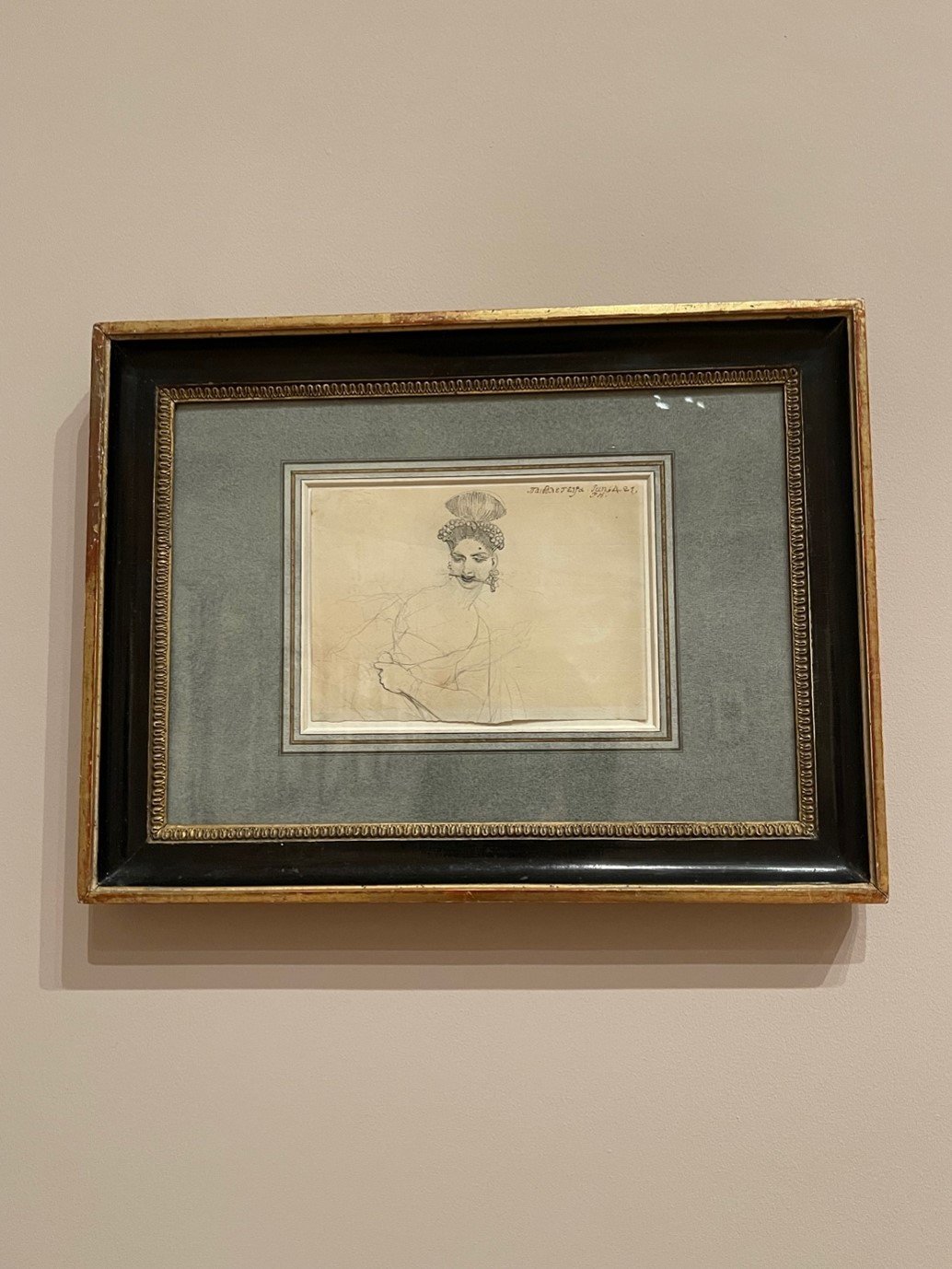

Fuseli further disrupts the perceptions of womanhood by turning women into powerful perpetrators who commit sadomasochistic acts. It has been suspected that this darker side of Fuseli’s imagination was influenced by the writings of Marquis de Sade. In ‘Paidoleteira’ (1821), the courtesan is depicted as committing infanticide using a hairpin and the drawing has a Greek inscription of ‘child murderer’. Similarly, in ‘Woman with long plaits teasing a figure trapped in a well ‘(1817), Fuseli positions the woman as powerful, not only presented by the subject matter itself but also the use of a hierarchical composition. Nevertheless, the empowerment of women in Fuseli’s can be questioned as it appears to serve and appeal to the tastes of the libertines, who likely would have been Fuseli’s clients, rather than giving genuine agency and autonomy to women. In addition, the ubiquitous male gaze not only penetrates his sadomasochistic imagination of women, but also his drawings of female fashion. A recurring motif in his work is the juxtaposition between geometric or phallic shaped hairstyles with an open, provocative display of the female body, which is particularly prominent in ‘Kallipyga’ (1790- 92).

Kallipyga Woman with long plaits teasing Paidoleteira

a figure trapped in a well

The exhibition ultimately opens a broader discussion of womanhood and who has the power to define it. Fundamentally, Fuseli as the artist, has the power to imagine and represent womanhood based on his fantasy. This, nevertheless, is a product of the broader social climate, as well as the preferences of his clients; upper-class men. Perceptions of womanhood continue to be written over by the male gaze in art, meaning that women in the drawings of Fuseli are empowered, but not dignified. Following further waves of feminism, as well as the rise of female artists in modern and contemporary art, increasingly we see perceptions of womanhood on a much more individualistic and personal basis, by women themselves. Artists such as Fuseli can be appreciated for their socially innovative nature, but should be admired whilst recognising their historical contingency.